What is Monkeypox?

Monkeypox is a viral zoonosis, meaning it is a disease that is transmitted from animals to humans. This virus belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus in the Poxviridae family, which also includes the variola virus—responsible for smallpox—and the vaccinia virus, used in the smallpox vaccine. First discovered in 1958 among laboratory monkeys in Copenhagen, Denmark, monkeypox’s initial instances were recorded in non-human primates, thus giving the virus its name. However, various species of rodents and other small mammals are now recognized as its primary hosts.

The first human case of monkeypox was found in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). It was during a time when smallpox eradication efforts were succeeding. Since then, monkeypox cases have been mostly confined to Central and West Africa, with the DRC experiencing the highest incidence rates. The incidence of monkeypox varies depending on the region and the presence of virus-hosting animals in the environment.

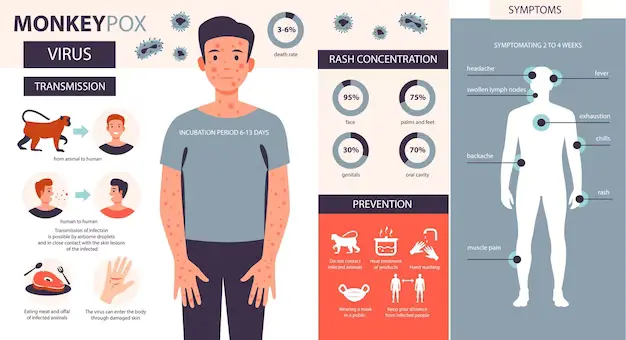

In terms of its clinical presentation, monkeypox symptoms are somewhat similar to those of smallpox, though typically less severe. The incubation period is 6 to 13 days. After that, patients have fever, a severe headache, swollen lymph nodes, back pain, muscle pain, and extreme weakness. A distinctive rash often emerges within one to three days of fever onset, starting on the face before spreading to other parts of the body, and eventually forming scabs.

Zoonotic transmission plays a critical role in the spread of monkeypox. Humans usually acquire the virus via direct contact with the blood, bodily fluids, or cutaneous or mucosal lesions of infected animals. Consuming undercooked meat and other animal products of infected animals is another route of infection. Secondary, human-to-human transmission can occur, though it is less common. It typically involves respiratory droplets, infected bodily fluids, or contaminated materials, like bedding.

Monkeypox Symptoms and Diagnosis

Monkeypox, an emerging viral threat, manifests through a distinct sequence of symptoms that can aid in timely diagnosis and management. The clinical presentation begins with an incubation period, typically ranging from 6 to 13 days, though it can extend up to 21 days in some cases. During this phase, the patient remains asymptomatic, with no visible signs of infection.

The first stage of monkeypox shows general symptoms like fever, severe headache, muscle and back pain. Additionally, the person may feel very tired and cold. Notably, swollen lymph nodes, or lymphadenopathy, appear in this stage. This sign sets monkeypox apart from similar diseases, such as smallpox.

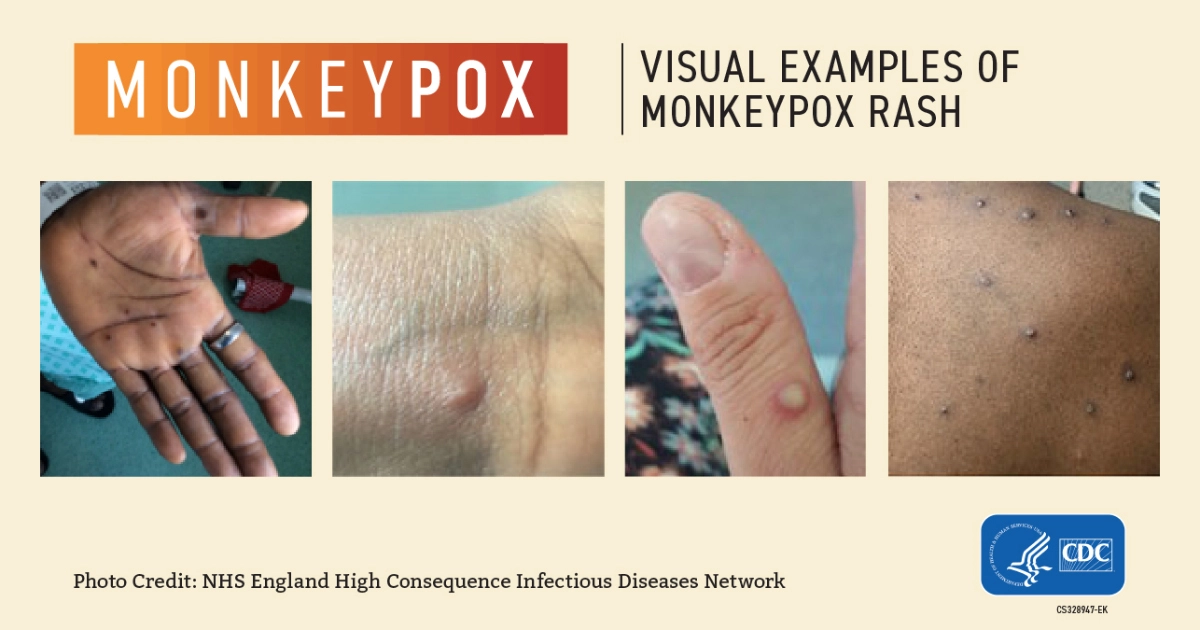

The infection leads to a rash 1 to 3 days after the fever starts. It first appears on the face, then spreads to the body, including the hands and feet. The rash develops in stages. It begins as flat, discolored spots. Then, it forms small blisters. Next, these blisters turn into pus-filled bumps. Finally, they crust over and fall off. This process takes 2 to 4 weeks.

Diagnosis of monkeypox involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory testing. Medical professionals rely on a patient’s travel history, exposure to infected animals, and the rash pattern for initial suspicion. Definitive diagnosis is confirmed through laboratory tests, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays that detect viral DNA. Serological tests may also support diagnosis, though PCR remains the gold standard.

Imaging techniques, like ultrasound, may help find enlarged lymph nodes. Differential diagnoses are essential to rule out similar conditions, such as chickenpox, measles, and bacterial skin infections. Early detection of monkeypox is crucial. It helps prevent complications, such as bacterial infections, pneumonia, and, in severe cases, encephalitis. Prompt diagnosis and intervention are vital to improving patient outcomes and controlling the spread of this viral threat.

Transmission and Prevention About Monkeypox

Monkeypox, an emerging viral threat, can be transmitted through several pathways. Primarily, the virus spreads via direct contact with the blood, bodily fluids, or cutaneous or mucosal lesions of infected humans or animals. This mode of transmission underscores the significance of personal interaction in the propagation of the disease. Additionally, respiratory droplets can facilitate the spread of monkeypox during prolonged face-to-face contact, presenting a considerable risk in densely populated settings. Moreover, fomites, which are objects or materials likely to carry infection, such as clothes, bedding, and personal items, can serve as conduits for the virus, further complicating control measures.

Geographic and demographic factors notably influence monkeypox outbreaks. Endemic regions, particularly in West and Central Africa, exhibit higher incidence rates due to the close proximity and interaction between humans and animals, especially rodents and primates, which are known reservoirs of the virus. Urbanization and deforestation also play crucial roles, escalating human-wildlife encounters and the subsequent risk of transmission. Demographically, individuals involved in caregiving, animal handling, and those in healthcare settings are at elevated risk.

Prevention protocols have been established to mitigate the spread of monkeypox. The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is paramount, especially for healthcare workers and individuals in direct contact with infected patients. Quarantine and isolation of confirmed cases curtail human-to-human transmission, while travel restrictions limit the spread of the virus across regions. Vaccination represents a vital tool in preventing monkeypox. Currently, the smallpox vaccine demonstrates cross-protection against monkeypox due to the genetic similarity between the two viruses. Moreover, newer vaccines specifically targeting monkeypox are under development, promising enhanced efficacy and safety.

Global Health Impact and Response

Monkeypox has increasingly become a significant public health concern on a global scale. The implications of monkeypox outbreaks are multifaceted, affecting communities, healthcare systems, and economies across different regions. The threats to already vulnerable populations are particularly alarming. They suffer most from healthcare disparities and limited access to medical resources. The impact on healthcare systems is profound. It demands rapid responses to prevent overwhelming hospitals. We must also protect and equip healthcare professionals to manage cases.

From an economic perspective, the ripple effects are unavoidable. Outbreaks often lead to decreased productivity, increased medical costs, and a general strain on economic stability, particularly in affected regions. Trade and travel are global. So, no country is immune to the economic impacts of disease outbreaks.

International health organizations, especially the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are leading efforts against monkeypox. They collaborate to create a unified response. Key strategies include surveillance to monitor and report new cases. Guidelines from WHO and CDC aid this process. Enhanced surveillance allows for early detection and limits the virus’s spread.

Communication campaigns are also pivotal, aiming to inform and educate the public about preventive measures, symptoms, and the importance of seeking timely medical attention. These campaigns use various media to reach diverse populations. This ensures wide dissemination of crucial information.

International health organizations lead research on monkeypox. They aim to understand its transmission, develop vaccines, and find effective treatments. Collaboration between countries and organizations has intensified, pooling resources and expertise to combat the disease more effectively.

Notable collaborative initiatives include data sharing programs, joint research projects, and coordinated response plans during outbreaks. These efforts highlight the need for a united global response to monkeypox. It will help us manage and control this emerging viral threat.